m (→External links: + category) |

No edit summary Tag: sourceedit |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

In his high school days, a classmate lent him a copy of ''Astounding Stories'', which was to be the start of Roddenberry's fascination with science fiction. (''[[The Making of Star Trek]]'') He studied three years of policemanship and then transferred his academic interest to aeronautical engineering and qualified for a pilot's license. He [[United States armed forces#Star Trek personalities with military service|volunteered]] for the United States Army Air Corps, and was ordered into training as a flying cadet when the United States entered the Second World War in 1941 |

In his high school days, a classmate lent him a copy of ''Astounding Stories'', which was to be the start of Roddenberry's fascination with science fiction. (''[[The Making of Star Trek]]'') He studied three years of policemanship and then transferred his academic interest to aeronautical engineering and qualified for a pilot's license. He [[United States armed forces#Star Trek personalities with military service|volunteered]] for the United States Army Air Corps, and was ordered into training as a flying cadet when the United States entered the Second World War in 1941 |

||

| − | Ordered to the South Pacific, Second Lieutenant Roddenberry flew missions against enemy strongholds. In all, he took part in approximately 89 missions and sorties. He was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. |

+ | Ordered to the South Pacific, Second Lieutenant Roddenberry flew missions against enemy strongholds. In all, he took part in approximately 89 missions and sorties. He was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. His pilot days were a source of pride for Roddenberry and, with the exception of [[Harold Livingston]], he famously got along well with others who shared a similar background.<ref>For other pilots among ''Star Trek'' personnel, see [[James Doohan]], [[Franz Bachelin]], [[Michael Dorn]], [[Matt Jefferies|Matt]] and [[John Jefferies]], [[Harold Livingston]] and [[Stephen Edward Poe]].</ref> |

It was in the South Pacific where he first began writing. He sold stories to flying magazines, and later poetry to publications, including ''The New York Times''. When the war ended, he joined the Pan American World Airways. During this time, he also studied literature at Columbia University. |

It was in the South Pacific where he first began writing. He sold stories to flying magazines, and later poetry to publications, including ''The New York Times''. When the war ended, he joined the Pan American World Airways. During this time, he also studied literature at Columbia University. |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

=== Television === |

=== Television === |

||

| − | He continued flying until he saw television for the first time. Correctly estimating television's future, he realized this new medium would need writers. He acted immediately, he went to Hollywood. He left his flying career behind, a decision aided by a 1947 incident (''[http://www.check-six.com/Crash_Sites/ClipperEclipse-NC88845.htm Check-Six.com - "The Clipper Eclipse"]''), when Roddenberry's Pan Am airplane crashed in the Syrian Desert, leaving only him and seven others surviving (''[[The Star Trek Compendium]]'', p 7). Although the accident really happened, Roddenberry largely exaggerated it in later life, claiming that he single-handedly rescued the survivors from the wreckage, fought raiding Arab tribesmen, and walked across the desert to the nearest phone and |

+ | He continued flying until he saw television for the first time. Correctly estimating television's future, he realized this new medium would need writers. He acted immediately, he went to Hollywood. He left his flying career behind, a decision aided by a 1947 incident (''[http://www.check-six.com/Crash_Sites/ClipperEclipse-NC88845.htm Check-Six.com - "The Clipper Eclipse"]''), when Roddenberry's Pan Am airplane crashed in the Syrian Desert, leaving only him and seven others surviving (''[[The Star Trek Compendium]]'', p 7). Although the accident really happened, Roddenberry largely exaggerated it in later life, claiming that he single-handedly rescued the survivors from the wreckage, fought raiding Arab tribesmen, and walked across the desert to the nearest phone and called for help. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'', p 14) |

Roddenberry arrived in Hollywood only to find television industry still in its infancy, with few openings for inexperienced writers. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department. While working his way up the LAPD ranks, he wrote his first script in {{y|1951}}. Later he sold scripts to shows such as ''Goodyear Theater'', ''The Kaiser Aluminum Hour'', ''Four Star Theater'', ''Dragnet'', ''The Jane Wyman Theater'', and ''Naked City''. Established as a writer, Sergeant Roddenberry turned in his badge and became a full-time writer in {{y|1956}}. (''[[Star Trek Creator]]'', p 141) |

Roddenberry arrived in Hollywood only to find television industry still in its infancy, with few openings for inexperienced writers. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department. While working his way up the LAPD ranks, he wrote his first script in {{y|1951}}. Later he sold scripts to shows such as ''Goodyear Theater'', ''The Kaiser Aluminum Hour'', ''Four Star Theater'', ''Dragnet'', ''The Jane Wyman Theater'', and ''Naked City''. Established as a writer, Sergeant Roddenberry turned in his badge and became a full-time writer in {{y|1956}}. (''[[Star Trek Creator]]'', p 141) |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

The first pilot was rejected by the network, pronounced "too cerebral". Once on the air, however, ''Star Trek'' developed a loyal following. Influenced by a fan write-in campaign, NASA even named its prototype space shuttle ''[[Enterprise (OV-101)|Enterprise]]'', in recognition of the ship that Roddenberry conceived for the series. |

The first pilot was rejected by the network, pronounced "too cerebral". Once on the air, however, ''Star Trek'' developed a loyal following. Influenced by a fan write-in campaign, NASA even named its prototype space shuttle ''[[Enterprise (OV-101)|Enterprise]]'', in recognition of the ship that Roddenberry conceived for the series. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Initially, Roddenberry served as the sole line producer on ''Star Trek'', working with associate producers [[Robert Justman]] and [[John D.F. Black]]. Aside from producing the series, Roddenberry was responsible for most of the rewriting done on scripts, which was necessary for getting stories into shape and merging them into the ''Star Trek'' format, as most writers weren't familiar with the series and its unique concept at the beginning. Justman described Roddenberry as actually being a much better re-writer than writer. However, many writers and even Black, whose script for {{e|The Naked Time}} got rewritten without asking for his permit, got awry with Roddenberry for what they considered to be a butchering of their work. (''[[These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One]]'', ''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'') |

||

| + | |||

| + | After Black's departure from the series in {{m|August|1966}}, Roddenberry, unable to cope with the demands of serving as sole producer and re-writer, hired [[Gene L. Coon]] to serve as line producer and stepped back to the position of executive producer. While still largely overseeing production and occasionally doing re-writes, most of the re-writing was now Coon's responsibility. Under Coon's watch, the series developed into what we now consider the classic ''Star Trek'' formula (including the introduction of such concepts as the [[United Federation of Planets]] and the [[Prime Directive]]), and also diverged into more light-hearted action-adventure than Roddenberry's dramatic approach. (''[[These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One]]'', ''[[These Are the Voyages: TOS Season Two]]'', ''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'') |

||

| + | |||

| + | In mid-[[TOS Season 2|season two]], Coon left the series, mainly because of his dispute with Roddenberry, who disliked his new, more comical approach to the series, and was replaced by [[John Meredyth Lucas]]. After ''Star Trek'' was saved from cancellation and a [[TOS Season 3|third season]] was commenced, Roddenberry promised to return to the show as line producer, if [[NBC]] promised him a new, more family-oriented timeslot of Mondays 7:30PM. However, when the network finally doomed ''Star Trek'' to the "graveyard slot" of Fridays 10PM, Roddenberry declined his offer, and eventually backed out from the series. With [[Fred Freiberger]] serving as line producer, Roddenberry - while keeping his title and salary of executive producer - relocated his office to the far side of the former [[Desilu]] lot, and kept away from managing the show in its third and last year. Justman said that the decline of script quality was mainly due to the fact that "the Roddenberry touch" was gone. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'') |

||

| + | |||

| + | In late-{{y|1967}} and early-{{y|1968}}, Roddenberry secretly funded and coordinated the letter-writing campaign initiated by [[Bjo Trimble]] and her husband, which succeeded in making NBC to renew ''Star Trek'' for a third season. The network and the public was told that it was a spontaneous action organized by fans, but Justman and [[Herb Solow]] debunked Roddenberry's involvement in their book ''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]''. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Roddenberry - with Trimble and his future wife [[Majel Barrett]] - also founded [[Lincoln Enterprises]] around this time, which specialized in selling ''Star Trek'' memorabilia to fans. One such memorabilia was unused, spliced up clips from the series' original 35mm film trims, which was taken by Roddenberry from the [[Desilu]] vaults. Solow was especially angered by this, accusing Roddenberry with stealing studio property for his own gain. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'') |

||

After the ''Star Trek'' series ended, Roddenberry produced several motion pictures, and also made a number of pilots for television. Roddenberry served as a member of the Writers Guild Executive Council and as a Governor of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. He held three honorary doctorate degrees: Doctor of Humane Letters from Emerson College (1977), Doctor of Literature from Union College in Los Angeles, and Doctor of Science from {{w|Clarkson University}} in Potsdam, New York (1981). |

After the ''Star Trek'' series ended, Roddenberry produced several motion pictures, and also made a number of pilots for television. Roddenberry served as a member of the Writers Guild Executive Council and as a Governor of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. He held three honorary doctorate degrees: Doctor of Humane Letters from Emerson College (1977), Doctor of Literature from Union College in Los Angeles, and Doctor of Science from {{w|Clarkson University}} in Potsdam, New York (1981). |

||

| Line 61: | Line 71: | ||

=== Other works === |

=== Other works === |

||

| − | After the original ''Star Trek'' ended, Roddenberry ventured on numerous other projects, most of them turning out to be failures. In 1968, Roddenberry was contracted to write and produce two feature films for {{w|National General Pictures}}, but the films were never made. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'', p 406) He wrote the screenplay for {{w|Roger Vadim}}'s 1971 film, ''Pretty Maids All in a Row'', which featured [[James Doohan]], [[William Campbell]] and his daughter |

+ | After the original ''Star Trek'' ended, Roddenberry ventured on numerous other projects, most of them turning out to be failures. In 1968, Roddenberry was contracted to write and produce two feature films for {{w|National General Pictures}}, but the films were never made. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'', p 406) He wrote the screenplay for {{w|Roger Vadim}}'s 1971 film, ''Pretty Maids All in a Row'', which featured [[James Doohan]], [[William Campbell]], and his daughter [[Dawn Roddenberry]] in the cast. |

In 1973, he wrote and produced a science fiction pilot entitled ''Genesis II'', which featured [[Mariette Hartley]], [[Ted Cassidy]], [[Percy Rodriguez]] and his wife, [[Majel Barrett]] in the cast, costumes by [[William Ware Theiss]], and was photographed by [[Jerry Finnerman]]. It was not picked up as a series, and a year later Roddenberry made another pilot out of the same idea, titled ''Planet Earth''. This time [[Robert Justman]] served as producer, [[Marc Daniels]] as director, and the cast included [[Diana Muldaur]], Ted Cassidy, Majel Barrett, [[Craig Hundley]], [[Patricia Smith]], and again costumes by Theiss. However, this pilot wasn't picked up by the network either. |

In 1973, he wrote and produced a science fiction pilot entitled ''Genesis II'', which featured [[Mariette Hartley]], [[Ted Cassidy]], [[Percy Rodriguez]] and his wife, [[Majel Barrett]] in the cast, costumes by [[William Ware Theiss]], and was photographed by [[Jerry Finnerman]]. It was not picked up as a series, and a year later Roddenberry made another pilot out of the same idea, titled ''Planet Earth''. This time [[Robert Justman]] served as producer, [[Marc Daniels]] as director, and the cast included [[Diana Muldaur]], Ted Cassidy, Majel Barrett, [[Craig Hundley]], [[Patricia Smith]], and again costumes by Theiss. However, this pilot wasn't picked up by the network either. |

||

| − | The same year, Roddenberry made another failed sci-fi pilot, ''The Questor Tapes'', which starred [[Robert Foxworth]] as an android, Questor, searching for his origins and creator. The pilot was directed by [[Richard Colla]] and also featured Majel Barrett and [[Walter Koenig]]. It was co-written by fellow ''Star Trek'' producer [[Gene L. Coon]]. ''The Questor Tapes'' was not picked up as a series, although its basic concept was reworked into the character of [[Data]] in ''Star Trek: The Next Generation''. Before returning to ''Trek'', Roddenberry made a fourth unsuccessful TV pilot, ''Spectre'' in 1977, about a detective involved in witchcraft and other occult |

+ | The same year, Roddenberry made another failed sci-fi pilot, ''The Questor Tapes'', which starred [[Robert Foxworth]] as an android, Questor, searching for his origins and creator. The pilot was directed by [[Richard Colla]] and also featured Majel Barrett and [[Walter Koenig]]. It was co-written by fellow ''Star Trek'' producer [[Gene L. Coon]]. ''The Questor Tapes'' was not picked up as a series, although its basic concept was reworked into the character of [[Data]] in ''Star Trek: The Next Generation''. Before returning to ''Trek'', Roddenberry made a fourth unsuccessful TV pilot, ''Spectre'' in 1977, about a detective involved in witchcraft and other occult phenomena. This pilot was co-written by [[Samuel A. Peeples]], and again featured Majel Barrett. |

=== The series that never was === |

=== The series that never was === |

||

| Line 174: | Line 184: | ||

*''[[Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation]]'' |

*''[[Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation]]'' |

||

*''[[The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry]]'' |

*''[[The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry]]'' |

||

| + | |||

| + | == Footnote == |

||

| + | <references/> |

||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

| Line 180: | Line 193: | ||

* [http://www.tv.com/gene-roddenberry/person/17703/biography.html Gene Roddenberry Biography and Stories] at [http://www.tv.com TV.com] |

* [http://www.tv.com/gene-roddenberry/person/17703/biography.html Gene Roddenberry Biography and Stories] at [http://www.tv.com TV.com] |

||

* {{NCwiki}} |

* {{NCwiki}} |

||

| + | * {{sf-encyc|roddenberry_gene}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Roddenberry, Gene}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Roddenberry, Gene}} |

||

| Line 199: | Line 213: | ||

[[Category:TOS performers]] |

[[Category:TOS performers]] |

||

[[Category:Writers]] |

[[Category:Writers]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hugo Award nominees]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hugo Award winners]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Writers Guild of America Award nominees]] |

||

Revision as of 11:13, 2 July 2015

Template:Realworld Eugene Wesley Roddenberry (19 August 1921 – 24 October 1991; age 70), sometimes referred to as the "Great Bird of the Galaxy" is best known as the creator of the science fiction television series Star Trek, beginning the long running Star Trek franchise. Roddenberry's remains (some of his ashes in a small capsule, about the size of a lipstick) were the first to be launched into Earth's orbit, where they orbited the Earth until they burned up while reentering the Earth's atmosphere.

Gene Roddenberry quotes

"I've never had a bad experience with a Trekkie."

- - Eugene Wesley Roddenberry, from Late Night America – 9/24/85 (as cited by Susan Sackett, used with permission)

History

Early life

Roddenberry was born in El Paso, Texas, on 19 August 1921 to Caroline Glen Roddenberry and Eugene Edward Roddenberry, and spent his childhood in the city of Los Angeles. His father was a police officer, whom he described as a "bigoted Texan". (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, p 14)

In his high school days, a classmate lent him a copy of Astounding Stories, which was to be the start of Roddenberry's fascination with science fiction. (The Making of Star Trek) He studied three years of policemanship and then transferred his academic interest to aeronautical engineering and qualified for a pilot's license. He volunteered for the United States Army Air Corps, and was ordered into training as a flying cadet when the United States entered the Second World War in 1941

Ordered to the South Pacific, Second Lieutenant Roddenberry flew missions against enemy strongholds. In all, he took part in approximately 89 missions and sorties. He was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. His pilot days were a source of pride for Roddenberry and, with the exception of Harold Livingston, he famously got along well with others who shared a similar background.[1]

It was in the South Pacific where he first began writing. He sold stories to flying magazines, and later poetry to publications, including The New York Times. When the war ended, he joined the Pan American World Airways. During this time, he also studied literature at Columbia University.

Roddenberry married his first wife, Eileen Anita Rexroat on 20 June 1942.

Television

He continued flying until he saw television for the first time. Correctly estimating television's future, he realized this new medium would need writers. He acted immediately, he went to Hollywood. He left his flying career behind, a decision aided by a 1947 incident (Check-Six.com - "The Clipper Eclipse"), when Roddenberry's Pan Am airplane crashed in the Syrian Desert, leaving only him and seven others surviving (The Star Trek Compendium, p 7). Although the accident really happened, Roddenberry largely exaggerated it in later life, claiming that he single-handedly rescued the survivors from the wreckage, fought raiding Arab tribesmen, and walked across the desert to the nearest phone and called for help. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, p 14)

Roddenberry arrived in Hollywood only to find television industry still in its infancy, with few openings for inexperienced writers. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department. While working his way up the LAPD ranks, he wrote his first script in 1951. Later he sold scripts to shows such as Goodyear Theater, The Kaiser Aluminum Hour, Four Star Theater, Dragnet, The Jane Wyman Theater, and Naked City. Established as a writer, Sergeant Roddenberry turned in his badge and became a full-time writer in 1956. (Star Trek Creator, p 141)

In 1963, Roddenberry began producing his first television series, The Lieutenant at MGM. The Lieutenant co-starred Gary Lockwood, and included many future Star Trek-alumni in guest roles, such as Leonard Nimoy, Majel Barrett, Nichelle Nichols, James Gregory and Madlyn Rhue. However, the series lasted only one season, and was cancelled in the spring of 1964.

Star Trek

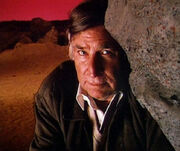

Roddenberry on set.

- See also: TOS: Behind the scenes

When The Lieutenant ended, Roddenberry began planning for his next series, a science fiction-adventure show entitled Star Trek. He wrote his series proposal, Star Trek is..., in March 1964. Initially proposed for MGM, the studio, although initially enthusiastic, refused to buy it. (The Star Trek Compendium, p 10) Finally Roddenberry sold his idea to Oscar Katz and Herb Solow of Desilu in April 1964. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, pp 15-16)

In 1965, Roddenberry also produced two other pilots for Desilu: The Long Hunt of April Savage, a western created by Sam Rolfe, starring Robert Lansing, and Police Story, featuring DeForest Kelley and Grace Lee Whitney. However, neither of them were picked up to become a series.

The first pilot was rejected by the network, pronounced "too cerebral". Once on the air, however, Star Trek developed a loyal following. Influenced by a fan write-in campaign, NASA even named its prototype space shuttle Enterprise, in recognition of the ship that Roddenberry conceived for the series.

Initially, Roddenberry served as the sole line producer on Star Trek, working with associate producers Robert Justman and John D.F. Black. Aside from producing the series, Roddenberry was responsible for most of the rewriting done on scripts, which was necessary for getting stories into shape and merging them into the Star Trek format, as most writers weren't familiar with the series and its unique concept at the beginning. Justman described Roddenberry as actually being a much better re-writer than writer. However, many writers and even Black, whose script for "The Naked Time" got rewritten without asking for his permit, got awry with Roddenberry for what they considered to be a butchering of their work. (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

After Black's departure from the series in August 1966, Roddenberry, unable to cope with the demands of serving as sole producer and re-writer, hired Gene L. Coon to serve as line producer and stepped back to the position of executive producer. While still largely overseeing production and occasionally doing re-writes, most of the re-writing was now Coon's responsibility. Under Coon's watch, the series developed into what we now consider the classic Star Trek formula (including the introduction of such concepts as the United Federation of Planets and the Prime Directive), and also diverged into more light-hearted action-adventure than Roddenberry's dramatic approach. (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, These Are the Voyages: TOS Season Two, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

In mid-season two, Coon left the series, mainly because of his dispute with Roddenberry, who disliked his new, more comical approach to the series, and was replaced by John Meredyth Lucas. After Star Trek was saved from cancellation and a third season was commenced, Roddenberry promised to return to the show as line producer, if NBC promised him a new, more family-oriented timeslot of Mondays 7:30PM. However, when the network finally doomed Star Trek to the "graveyard slot" of Fridays 10PM, Roddenberry declined his offer, and eventually backed out from the series. With Fred Freiberger serving as line producer, Roddenberry - while keeping his title and salary of executive producer - relocated his office to the far side of the former Desilu lot, and kept away from managing the show in its third and last year. Justman said that the decline of script quality was mainly due to the fact that "the Roddenberry touch" was gone. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

In late-1967 and early-1968, Roddenberry secretly funded and coordinated the letter-writing campaign initiated by Bjo Trimble and her husband, which succeeded in making NBC to renew Star Trek for a third season. The network and the public was told that it was a spontaneous action organized by fans, but Justman and Herb Solow debunked Roddenberry's involvement in their book Inside Star Trek: The Real Story.

Roddenberry - with Trimble and his future wife Majel Barrett - also founded Lincoln Enterprises around this time, which specialized in selling Star Trek memorabilia to fans. One such memorabilia was unused, spliced up clips from the series' original 35mm film trims, which was taken by Roddenberry from the Desilu vaults. Solow was especially angered by this, accusing Roddenberry with stealing studio property for his own gain. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

After the Star Trek series ended, Roddenberry produced several motion pictures, and also made a number of pilots for television. Roddenberry served as a member of the Writers Guild Executive Council and as a Governor of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. He held three honorary doctorate degrees: Doctor of Humane Letters from Emerson College (1977), Doctor of Literature from Union College in Los Angeles, and Doctor of Science from Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York (1981).

For Star Trek's 25th anniversary, two months before his death, Roddenberry gave TV Guide a list of his top ten favorite episodes. One might assume that these most clearly represented his vision of what Star Trek should be:

- "Amok Time"

- "Balance of Terror"

- "The City on the Edge of Forever"

- "The Devil in the Dark"

- "The Enemy Within"

- "The Menagerie, Part I" and "The Menagerie, Part II"

- "The Naked Time"

- "The Return of the Archons"

- "Where No Man Has Gone Before"

- "The Trouble with Tribbles"

Other works

After the original Star Trek ended, Roddenberry ventured on numerous other projects, most of them turning out to be failures. In 1968, Roddenberry was contracted to write and produce two feature films for National General Pictures, but the films were never made. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, p 406) He wrote the screenplay for Roger Vadim's 1971 film, Pretty Maids All in a Row, which featured James Doohan, William Campbell, and his daughter Dawn Roddenberry in the cast.

In 1973, he wrote and produced a science fiction pilot entitled Genesis II, which featured Mariette Hartley, Ted Cassidy, Percy Rodriguez and his wife, Majel Barrett in the cast, costumes by William Ware Theiss, and was photographed by Jerry Finnerman. It was not picked up as a series, and a year later Roddenberry made another pilot out of the same idea, titled Planet Earth. This time Robert Justman served as producer, Marc Daniels as director, and the cast included Diana Muldaur, Ted Cassidy, Majel Barrett, Craig Hundley, Patricia Smith, and again costumes by Theiss. However, this pilot wasn't picked up by the network either.

The same year, Roddenberry made another failed sci-fi pilot, The Questor Tapes, which starred Robert Foxworth as an android, Questor, searching for his origins and creator. The pilot was directed by Richard Colla and also featured Majel Barrett and Walter Koenig. It was co-written by fellow Star Trek producer Gene L. Coon. The Questor Tapes was not picked up as a series, although its basic concept was reworked into the character of Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Before returning to Trek, Roddenberry made a fourth unsuccessful TV pilot, Spectre in 1977, about a detective involved in witchcraft and other occult phenomena. This pilot was co-written by Samuel A. Peeples, and again featured Majel Barrett.

The series that never was

Roddenberry with his two personal assistants, Susan Sackett and Ernie Over

Roddenberry interviewed by Entertainment Tonight in 1991.

By June 1977, Star Trek was to become a television series again, after the success of the original Star Trek. Paramount attempted to launch a new series, tentatively titled Star Trek: Phase II. Construction on the sets started in July, and the writers' and directors' guide was published in August. The original cast, except for Leonard Nimoy, returned to reprise their roles, along with several new characters, such as Lt. Xon, who would be taking Spock's place, first officer Willard Decker, and navigator Lt. Ilia.

As work was being finished on the sets and costumes, Paramount abandoned the plans. Probably influenced by the success of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, they decided to turn the television series into Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

The Next Generation

In September 1987, Star Trek: The Next Generation continued the legend that Roddenberry began 25 years prior with Star Trek, the original series. This new show offered Roddenberry the technical possibilities and the budget to realize his vision.

On 6 June 1991 shortly before celebrating the 100th episode of The Next Generation the Producers Building at the former Desilu studio lot was renamed "Gene Roddenberry Building". Then Paramount Television Group president Mel Harris held a speech and during the ceremony William Shatner and Patrick Stewart said a few words about Roddenberry.

Legacy

The launch of the Columbia carrying the ashes of Roddenberry.

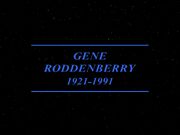

Memoriam credit for Gene Roddenberry during the opening of TNG: "Unification I" and TNG: "Unification II"

On 24 October 1991, Gene Roddenberry passed away, succumbing to cardiac arrest. At the time of his passing, Roddenberry was survived by his wife Majel Barrett, their son Eugene Roddenberry Jr., his two grown daughters from a previous marriage, Dawn Roddenberry and Darleen Roddenberry, and two grandchildren.

The ashes of Roddenberry were aboard the space shuttle Columbia during its start from the Kennedy Space Center on 22 October 1992.

Eugene Roddenberry, Jr. currently heads the Roddenberry.com website which is also the main site for Lincoln Enterprises), and is "Consulting Producer" for the fan film series Star Trek: New Voyages.

The legacy of Star Trek, as created by Gene Roddenberry, continued to grow as the newest series, Star Trek: Enterprise, joined Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Star Trek: Voyager. Star Trek: The Next Generation evolved into a feature film series, debuting in 1994 with Star Trek Generations.

Other shows of Roddenberry's design include Earth: Final Conflict and Andromeda, which was based on a 1973 pilot he produced called Genesis II (with Mariette Hartley, Majel Barrett, Percy Rodriguez and Ted Cassidy) and its 1974 re-working Planet Earth (with Barrett, Cassidy, Diana Muldaur, and Craig Hundley).

Roddenberry canon

A minority of purist fans advocate a "Roddenberry canon" to denote what episodes Star Trek's creator approved of as "official." Defining such a concept is elusive, as Roddenberry was known to change his views over the years. The Original Series would seem to be part of this canon, comprising 79 episodes, plus the un-aired pilot ("The Cage"). He rejected The Animated Series as apocryphal, along with elements of two films, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. At the time of his death, 110 episodes of The Next Generation had completed production, from "Encounter at Farpoint" through "New Ground". This leaves 190 episodes of Star Trek as part of the supposed Roddenberry canon, along with the first four films, and most of films five and six. Adhering to this view would mean rejecting 536 episodes, as well as at least four films, as there have been 726 episodes of Star Trek produced to date, along with twelve motion pictures.

Trivia

- Gene Roddenberry had a second cousin twice removed named Mary Sue Roddenberry. Ironically, and probably by sheer coincidence, the widespread fan fiction term "Mary Sue", which is used to describe overly perfect original female characters, has its origins in the person of Lt. Mary Sue, a character in the satirical 1974 short Star Trek story by Paula Smith called "A Trekkie's Tale".

- Roddenberry gave his middle name to one of the characters of Star Trek: The Next Generation – Wesley Crusher. (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, p. 14) His middle name was also used as the last name of the TOS character Robert Wesley, which was also a pseudonym Roddenberry used in his early writing career. (Star Trek Encyclopedia 1st ed., p. 374) In addition, after his death, the creators of "Star Trek: Voyager" used Roddenberry's full first name as the middle name of reformed renegade officer Thomas Eugene Paris. (Star Trek Encyclopedia 3rd ed., p. 348)

- In "The Big Goodbye", an illustration of Gene Roddenberry was seen when Data was assimilating the Dixon Hill novels. This illustration was the copy of a photo of Gene Roddenberry.

Credits

Roddenberry's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Roddenberry receives a "Created by" credit on episodes of TOS and TNG. In addition he is credited on all episodes of DS9, VOY, and ENT, all the movies, and many Star Trek computer games such as the Elite Force series and Star Trek: Bridge Commander, via the phrase "Based upon Star Trek, created by Gene Roddenberry".

The first two TNG episodes aired after his death, "Unification I" and "Unification II" begin with the title card "Gene Roddenberry 1921 - 1991". Also, the film Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country begins with the credit, "For Gene Roddenberry". The credits for Star Trek end with "In memory of Gene Roddenberry and Majel Barrett Roddenberry". Several other Trek related products, including the video game Star Trek: 25th Anniversary include special thanks credits in honor of Roddenberry.

Roddenberry also receives credit for writing lyrics to the TOS main title theme, although these lyrics were never recorded in connection with the series. In the book Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, Herb Solow and Robert Justman allege that Roddenberry, who had no musical experience of any kind, wrote words to Alexander Courage's theme for the show solely to accrue royalties that were required to be paid to the lyricist. In doing so, he effectively cut Courage's royalties in half, as the composer would otherwise have received all royalties accruing from the theme. Courage was outraged on this, and refused to compose music for the series until the third season.

Roddenberry also credited himself as the co-author of the reference book The Making of Star Trek, which was written by Stephen E. Whitfield, and given to Roddenberry to make his corrections and edits, but he had no time to do it because of production deadlines. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

- Writing credits

- TOS:

- "The Cage"

- "Mudd's Women" (Story) (Season 1)

- "Charlie X" (Story)

- "The Menagerie, Part I"

- "The Menagerie, Part II"

- "The Return of the Archons" (Story)

- "Bread and Circuses" (with Gene L. Coon) (Season 2)

- "A Private Little War" (Teleplay with Gene L. Coon)

- "The Omega Glory"

- "Assignment: Earth" (Story with Art Wallace)

- "The Savage Curtain" (Teleplay with Arthur Heinemann, Story) (Season 3)

- "Turnabout Intruder" (Story)

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture (story, uncredited)

- TNG:

- "Encounter at Farpoint" (with D.C. Fontana) (Season 1)

- "Hide and Q" (Teleplay with C.J. Holland)

- "Datalore" (Teleplay with Robert Lewin)

- TOS:

- Producer credits

- TOS: (executive producer; producer)

- "The Cage" to "The Enemy Within" (producer)

- "The Man Trap" (credited as executive producer and producer)

- "Charlie X" to "Dagger of the Mind" (producer)

- "Miri" to "The Menagerie, Part I" (executive producer)

- "The Menagerie, Part II" (producer - credit for "The Cage")

- "Shore Leave" to "The Omega Glory" (executive producer)

- "Assignment: Earth" (producer)

- "Spectre of the Gun" to "Turnabout Intruder" (executive producer)

- TAS (executive producer)

- Star Trek films:

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture (producer)

- TNG (executive producer) from "Encounter at Farpoint" to "Time's Arrow"

- (posthumous credit only from "Violations" to "Time's Arrow")

- TOS: (executive producer; producer)

- Executive consultant credits

- Acting credits

- TOS:

- "Charlie X" as the voice of the galley chef (uncredited) (Star Trek Encyclopedia, etc.)

- In addition, Roddenberry hosted the video release of "The Cage" and an image of him appeared as Captain Robert April in the Star Trek Encyclopedia. He can also be heard (along with Majel Barrett and other production people) in the background intercom chatter in "Where No Man Has Gone Before" (and subsequent episodes reusing the same sound tracks).

- TOS:

Interviews

Interviews of Roddenberry were part of the following specials:

- The Star Trek Saga: From One Generation To The Next, interviewed on 20 September 1988

- TNG Season 1 DVD special feature "The Beginning"

- TNG Season 1 DVD special feature "Memorable Missions"

- TNG Season 2 DVD special feature "Mission Overview Year Two" ("Diana Muldaur", "Whoopi Goldberg"), footage taken from The Star Trek Saga...

- TNG Season 2 DVD special feature "Selected Crew Analysis Year Two", footage taken from The Star Trek Saga...

- TNG Season 4 DVD special feature "Mission Overview Year Four" ("Celebrating 100 Episodes"), interviewed by Entertainment Tonight in 1991

- TNG Season 5 DVD special feature "A Tribute to Gene Roddenberry" ("Gene Roddenberry Building Dedicated to Star Trek's Creator", "Gene's Final Voyage"), interviewed on 6 June 1991 and footage taken from The Star Trek Saga...

- To Boldly Go

- "Gene Roddenberry - The Creator of Star Trek: The Next Generation", The Official Star Trek: The Next Generation Magazine Vol. 1, pp. 4-9, interviewed by Dan Madsen, John S. Davis and Dan Dickholtz

- "Eternal Questions", The Official Star Trek: The Next Generation Magazine Vol. 11, p. 15

See also

Footnote

- ↑ For other pilots among Star Trek personnel, see James Doohan, Franz Bachelin, Michael Dorn, Matt and John Jefferies, Harold Livingston and Stephen Edward Poe.

External links

- Gene Roddenberry at Wikipedia

- Template:IMDb-link

- Gene Roddenberry Biography and Stories at TV.com

- Template:NCwiki

- Gene Roddenberry at SF-Encyclopedia.com