m (→Credits: grm.) Tag: sourceedit |

m (→Credits: grm.) Tag: sourceedit |

||

| Line 150: | Line 150: | ||

The first two ''Next Generation'' episodes aired after his death, {{e|Unification I}} and {{e|Unification II}} begin with the title card "Gene Roddenberry 1921 - 1991". Also, the film ''The Undiscovered Country'' begins with the credit, "For Gene Roddenberry". The credits for {{film|11}} end with "In memory of Gene Roddenberry and Majel Barrett Roddenberry". Several other ''Trek'' related products, including the video game ''{{dis|Star Trek: 25th Anniversary|PC}}'' include special thanks credits in honor of Roddenberry. |

The first two ''Next Generation'' episodes aired after his death, {{e|Unification I}} and {{e|Unification II}} begin with the title card "Gene Roddenberry 1921 - 1991". Also, the film ''The Undiscovered Country'' begins with the credit, "For Gene Roddenberry". The credits for {{film|11}} end with "In memory of Gene Roddenberry and Majel Barrett Roddenberry". Several other ''Trek'' related products, including the video game ''{{dis|Star Trek: 25th Anniversary|PC}}'' include special thanks credits in honor of Roddenberry. |

||

| − | Roddenberry also receives credit for writing lyrics to the ''Original Series'' main title theme, although these lyrics were never recorded in connection with the series. In the reference book ''Inside Star Trek: The Real Story'' (1997, p. 185), Herb Solow and Robert Justman allege that Roddenberry, who had no musical experience of any kind, wrote words to [[Alexander Courage]]'s theme for the show solely to accrue royalties that were required to be paid to the lyricist. In doing so, he effectively cut Courage's royalties in half, as the composer would otherwise have received all royalties accruing from the theme. Courage was outraged on this, and left the production, only to return to score two episodes in the third season as a courtesy to Robert Justman. However, Courage mellowed over the years, has stated in his twilight years, "''There wasn't any rift, really, with Gene. What happened with Gene was a I got a phone call once...it was Gene's lawyer, [Leonard] Maizlish. He said, "I'm calling you to tell you that since you signed a piece of paper back there saying that if Gene ever wrote a lyric to your theme that he would split your royalties on the theme." Gene and I weren’t enemies in any sort of way. It was just one of those things...I think it was Maizlish, probably, who put him up to doing it that way, and it's a shame, because actually if he'd written a decent lyric we could have both made more money.''" [http://www.emmytvlegends.org/interviews/people/alexander-courage#] Having corresponded with Courage at a later point in time, this was another example of Roddenberry's more amiable character traits; whenever he felt that he had aggrieved someone, he often felt the need to make amends afterwards, like he had done with Robert Justman as described above. The Roddenberry/Maizlish duo had actually tried to do something similar with Leonard Nimoy's first vinyl album recording, ''Mr. Spock's Music From Outer Space'', which marked the beginning of the descent into animosity of the relationship between Roddenberry and Nimoy. With Nimoy however, Roddenberry was not able to mend fences, due to a continuous series of subsequent incidents (such as in the instance of ''The Questor Tapes'', mentioned above), which kept bedeviling any possible chance of reconciliation. After ''The Motion Picture'', |

+ | Roddenberry also receives credit for writing lyrics to the ''Original Series'' main title theme, although these lyrics were never recorded in connection with the series. In the reference book ''Inside Star Trek: The Real Story'' (1997, p. 185), Herb Solow and Robert Justman allege that Roddenberry, who had no musical experience of any kind, wrote words to [[Alexander Courage]]'s theme for the show solely to accrue royalties that were required to be paid to the lyricist. In doing so, he effectively cut Courage's royalties in half, as the composer would otherwise have received all royalties accruing from the theme. Courage was outraged on this, and left the production, only to return to score two episodes in the third season as a courtesy to Robert Justman. However, Courage mellowed over the years, has stated in his twilight years, "''There wasn't any rift, really, with Gene. What happened with Gene was a I got a phone call once...it was Gene's lawyer, [Leonard] Maizlish. He said, "I'm calling you to tell you that since you signed a piece of paper back there saying that if Gene ever wrote a lyric to your theme that he would split your royalties on the theme." Gene and I weren’t enemies in any sort of way. It was just one of those things...I think it was Maizlish, probably, who put him up to doing it that way, and it's a shame, because actually if he'd written a decent lyric we could have both made more money.''" [http://www.emmytvlegends.org/interviews/people/alexander-courage#] Having corresponded with Courage at a later point in time, this was another example of Roddenberry's more amiable character traits; whenever he felt that he had aggrieved someone, he often felt the need to make amends afterwards, like he had done with Robert Justman as described above. The Roddenberry/Maizlish duo had actually tried to do something similar with Leonard Nimoy's first vinyl album recording, ''Mr. Spock's Music From Outer Space'', which marked the beginning of the descent into animosity of the relationship between Roddenberry and Nimoy. With Nimoy however, Roddenberry was not able to mend fences, due to a continuous series of subsequent incidents (such as in the instance of ''The Questor Tapes'', mentioned above), which kept bedeviling any possible chance of reconciliation. After ''The Motion Picture'', were he finally had his pound of flesh by conspiring against Roddenberry, Nimoy broke off any communication between them, and both were not seen together afterwards, save for the subsequent five ''Original Crew'' films at official studio press presentations. Nimoy has not been present at any commemorative event involving Roddenberry, nor was he present at his funeral. |

Roddenberry also credited himself as the co-author of the reference book ''[[The Making of Star Trek]]'', receiving half the royalties, which was written by [[Stephen E. Whitfield]], and given to Roddenberry to make his corrections and edits, though he had never the time to do so, because of production deadlines. While virtually every other person (like the above-mentioned Courage), before or after, who had been cajoled out of their royalty shares in a similar way by Roddenberry, became livid with him, Whitfield (''aka'' [[Stephen Edward Poe]]), was ''the'' notable exception. Not minding surrendering half the book royalties, Whitfield got along very well with Roddenberry, not in the least due to their shared aviation background, and was grateful for the chance he was given to start his writing career as a book author. The fact that he had written the very first ''Star Trek'' reference book (and a very successful one at that) had been a source of immense pride for him for the remainder of his life. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'', 1997, pp. 401-402) |

Roddenberry also credited himself as the co-author of the reference book ''[[The Making of Star Trek]]'', receiving half the royalties, which was written by [[Stephen E. Whitfield]], and given to Roddenberry to make his corrections and edits, though he had never the time to do so, because of production deadlines. While virtually every other person (like the above-mentioned Courage), before or after, who had been cajoled out of their royalty shares in a similar way by Roddenberry, became livid with him, Whitfield (''aka'' [[Stephen Edward Poe]]), was ''the'' notable exception. Not minding surrendering half the book royalties, Whitfield got along very well with Roddenberry, not in the least due to their shared aviation background, and was grateful for the chance he was given to start his writing career as a book author. The fact that he had written the very first ''Star Trek'' reference book (and a very successful one at that) had been a source of immense pride for him for the remainder of his life. (''[[Inside Star Trek: The Real Story]]'', 1997, pp. 401-402) |

||

Revision as of 12:34, 3 August 2015

Template:Realworld Eugene Wesley Roddenberry (19 August 1921 – 24 October 1991; age 70), sometimes referred to as the "Great Bird of the Galaxy" is best known as the creator of the science fiction television series Star Trek, beginning the long running Star Trek franchise. Roddenberry's remains (some of his ashes in a small capsule, about the size of a lipstick) were the first to be launched into Earth's orbit, where they orbited the Earth until they burned up while reentering the Earth's atmosphere.

Gene Roddenberry quotes

"If man is to survive, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures. He will learn that differences in ideas and attitudes are a delight, part of life's exciting variety, not something to fear."

- - Eugene Wesley Roddenberry, as quoted in an Aardvarque greeting card, Santa Barbara, CA, 1971 (as cited by Susan Sackett, used with permission)

History

Early life

Roddenberry was born in El Paso, Texas, on 19 August 1921 to Caroline Glen Roddenberry and Eugene Edward Roddenberry, and spent his childhood in the city of Los Angeles. His father was a police officer, whom he described as a "bigoted Texan". (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, p 14)

In his high school days, a classmate lent him a copy of Astounding Stories, which was to be the start of Roddenberry's fascination with science fiction. (The Making of Star Trek) He studied three years of policemanship and then transferred his academic interest to aeronautical engineering and qualified for a pilot's license. He volunteered for the United States Army Air Corps, and was ordered into training as a flying cadet when the United States entered the Second World War in 1941

Ordered to the South Pacific, Second Lieutenant Roddenberry flew missions against enemy strongholds. In all, he took part in approximately 89 missions and sorties. He was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. His pilot days were a source of pride for Roddenberry and, with the exception of Harold Livingston, he famously got along well with others who shared a similar background.[1]

It was in the South Pacific where he first began writing. He sold stories to flying magazines, and later poetry to publications, including The New York Times. When the war ended, he joined the Pan American World Airways. During this time, he also studied literature at Columbia University.

Roddenberry married his first wife, Eileen Anita Rexroat on 20 June 1942 in community of property, the latter of which to haunt Roddenberry for the remainder of his life. The marriage turned out to be a very unhappy one, in no small part due to Roddenberry's notorious philandering, both real and imagined.

He continued flying until he saw television for the first time. Correctly estimating television's future, he realized this new medium would need writers. He acted immediately, he went to Hollywood. He left his flying career behind, a decision aided by a 1947 incident, when Roddenberry's Pan Am airplane crashed in the Syrian Desert, leaving only him and seven others surviving. ([1]; The Star Trek Compendium, p. 7) Although the accident really happened, Roddenberry largely exaggerated it in later life, claiming that he single-handedly rescued the survivors from the wreckage, fought raiding Arab tribesmen, and walked across the desert to the nearest phone and called for help. The tale as recounted by Roddenberry was reminiscent of events depicted in the 1965 movie The Flight of the Phoenix. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, p. 14)

Television

Roddenberry arrived in Hollywood only to find television industry still in its infancy, with few openings for inexperienced writers. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department. While working his way up the LAPD ranks, he wrote his first script in 1951. Later he sold scripts to shows such as Goodyear Theater, The Kaiser Aluminum Hour, Four Star Theater, Dragnet, The Jane Wyman Theater, and Naked City. Established as a writer, Sergeant Roddenberry turned in his badge and became a full-time writer in 1956. (Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, p. 141)

Three years later, on 13 February 1959, he had his life-long accountant Mort Kessler establish his production company Norway Corporation, Inc., through which Roddenberry from here on end handled his business and legal dealings with the motion picture industry. [2] Roddenberry, hired young attorney Leonard Maizlish, to handle the legal aspects of his production company. From now on Roddenberry's life-long attorney, Maizlish was to have his presence felt on Star Trek. [3]

In 1963, Roddenberry began producing his first television series, The Lieutenant at MGM. The Lieutenant co-starred Gary Lockwood, and included many future Star Trek-alumni in guest roles, such as Leonard Nimoy, Majel Barrett, Nichelle Nichols, James Gregory and Madlyn Rhue. However, the series lasted only one season, and was canceled in the spring of 1964.

It was during this period in time that Roddenberry started his illicit affair with Majel Barret. (Star Trek Memories, p. 14) Already known of having marital problems as well as having been a "ladies man" with the LAPD secretarial staff during his police days, which otherwise remained unsubstantiated (Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, pp. 123, 163), Roddenberry concurrently started a romantic affair with Nichols, who in her own words therefore became "the other woman to the other woman". The Nichols-Roddenberry pair kept their relationship a closely guarded secret (though not closely enough as rumors of his romantic dalliances, including the one he had with Nichols, abounded on the Original Series stages throughout the entire production run, as related in the reference book, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story), except for Barrett, because of the possible impact their interracial relationship could have had on Roddenberry's career. Ultimately, Nichols decided to break off the relationship at the start of the Original Series, in order to make room for Barrett as well as falling in love with another man herself, even though Roddenberry wanted to continue an "open" relationship with both women at the same time. Nichols remained close friends with Roddenberry, and out of respect for him, did not came forward with the particulars until after his death. (Beyond Uhura, pp. 130-133)

Star Trek

On the set of "The Cage" with Solow (r) and three extras, "lamenting" the absence of Katz

- See also: TOS: Behind the scenes

When The Lieutenant ended, Roddenberry began planning for his next series, a science fiction-adventure show entitled Star Trek. He wrote his series proposal, Star Trek is..., in March 1964. Initially proposed for MGM, the studio, although initially enthusiastic, refused to buy it. (The Star Trek Compendium, p. 10) Finally Roddenberry sold his idea to Oscar Katz and Herb Solow of Desilu in early April 1964. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, pp. 15-16) It was Katz who accompanied Roddenberry in late April 1964 to the pitch he had arranged at television network CBS, Katz's former employer, shortly after Desilu had bought Roddenberry's premise. However, on that occasion, Katz took a backseat and an awkward and hopelessly unprepared Roddenberry, left to his own devices, seriously bumbled his presentation. Much later, Katz himself recalled the meeting as "frosty", "We were in a dining room with six or seven executives, one of whom questioned us rather closely about what we were going to do with the show. We answered his questions and it turned out that his interest was due to the fact that they were developing a science fiction show of their own." (Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry) Much to the later chagrin of Roddenberry, who felt that his brain had been picked, this show turned out to be Irwin Allen's Lost in Space. Unsurprisingly, CBS was not interested, as ABC had previously been due to the fact that they already had another Allen science fiction show, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, in development themselves. Dismayed, as CBS represented the best chance Star Trek had, due to the network's longstanding relationship with Desilu (CBS aired Ball's own I Love Lucy show), Solow subsequently took over after being informed of this, and thoroughly groomed, prepared and coached Roddenberry for his next, very last-chance, meeting with NBC the following month, as well as taking an active part in the presentation, which eventually resulted in success. Yet, the first pilot, "The Cage", was rejected by NBC, being pronounced as "too cerebral". This should have been the end of Star Trek there and then, but, in a for the industry hitherto unprecedented move, the network ordered a second pilot, which eventually led to the series being picked up by them.

In 1965, after "The Cage" and before he started on the second Star Trek pilot, Roddenberry also produced two other pilots for Desilu: The Long Hunt of April Savage, a western created by Sam Rolfe, starring Robert Lansing, and produced and co-wrote Police Story, featuring DeForest Kelley, Grace Lee Whitney, directed by Vincent McEveety, with music by Alexander Courage. However, neither of them were picked up to become a series, though April Savage came close as network ABC actually picked up the series, but decided to cancel the series after all, before regular series production was slated to begin.

After the second Star Trek pilot "Where No Man Has Gone Before" was picked up by NBC, Roddenberry entered into a formal contract with Desilu on 18 May 1965 where it was specified that he was entitled, besides his regular salary, to 26⅔% of the net profits derived from the series, which, as it turned, were not to materialize for him personally in the coming two decades. [4] However, neither Roddenberry nor Star Trek were out of the woods yet. Unexpectedly confronted with the production of three expensive television properties, which aside from Star Trek and April Savage also included Mission Impossible, all of them brought in by Katz and Solow (who were specifically hired to do so, in order to safeguard the future existence of the ailing studio), where there had only been one before, the I Love Lucy show, the conservative board of directors feared, not unjustified, that the small studio would financially overstretch itself. Vigorously defended by Solow (who wisely had left Roddenberry out of the meeting as the latter had seriously bumbled his Star Trek pitch to network CBS two years previously, but who firmly believed in the show), and despite the fact that Star Trek was ordered by NBC, the entire Desilu board unanimously voted to cancel Star Trek in February 1966 nevertheless. Yet, as Chairwoman of the Board, Lucille Ball had the power to override her board, and this she did with a mere nod of her head. "That was all Star Trek needed," as author Marc Cushman had succinctly put it, "A nod of Lucille Ball." (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, 1st ed, pp. 32, 94) One of the nay-sayers on the board, studio accountant Edwin "Ed" Holly, later conceded, "If it were not for Lucy, there would be no 'Star Trek' today." [5] Ironically, the fears of the board were somewhat allayed by the subsequent cancellation of April Savage. For all intents and purposes, and contrary to widely held beliefs in Star Trek-lore, this was factually the very first time that the Original Series came exceedingly close to cancellation. Once on the air however, Star Trek developed a loyal following. Much later, influenced by a fan write-in campaign, NASA even named its prototype space shuttle Enterprise, in recognition of the ship that Roddenberry conceived for the series.

Initially, Roddenberry served as the sole line producer on Star Trek, working with associate producers Robert Justman and John D.F. Black. Aside from producing the series, Roddenberry was responsible for most of the rewriting done on scripts, which was necessary for getting stories into shape and merging them into the Star Trek format, as most writers weren't familiar with the series and its unique concept at the beginning. Justman described Roddenberry as actually being a much better re-writer than writer. However, many writers and even Black, whose script for "The Naked Time" got rewritten without asking for his permit, got awry with Roddenberry for what they considered to be a butchering of their work. (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

After Black's departure from the series in August 1966, Roddenberry, unable to cope with the demands of serving as sole producer and re-writer, hired Gene L. Coon to serve as line producer and stepped back to the position of executive producer. While still largely overseeing production and occasionally doing re-writes, most of the re-writing was now Coon's responsibility. Under Coon's watch, the series developed into what we now consider the classic Star Trek formula (including the introduction of such concepts as the United Federation of Planets, the Prime Directive and, most notably, the Klingons), and also diverged into more light-hearted action-adventure than Roddenberry's dramatic approach. (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, These Are the Voyages: TOS Season Two, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

In mid-season two, Coon left the series, mainly because of his dispute with Roddenberry, who disliked his new, more comical approach to the series, and was replaced by John Meredyth Lucas. After Star Trek was saved from cancellation and a third season was commenced, Roddenberry promised to return to the show as line producer, if NBC promised him a new, more family-oriented timeslot of Mondays 7:30PM. However, when the network finally doomed Star Trek to the "graveyard slot" of Fridays 10PM, Roddenberry, having stated at the time to a newspaper, "If the network wants to kill us, it couldn't make a better move." (Toledo Blade, 15 August 1968), eventually backed out from the series. With Fred Freiberger serving as line producer, Roddenberry - while keeping his title and salary of executive producer - relocated his office to the far side of the former Desilu lot (as it was now the Paramount Pictures lot after Gulf+Western acquired Desilu in June 1967), and recused himself from managing the show in its third and last year. Justman said that the decline of script quality was mainly due to the fact that "the Roddenberry touch" was gone. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story)

The saving of Star Trek constituted the by Roddenberry secretly funded and coordinated letter-writing campaign, initiated by Bjo Trimble and her husband in late-1967 and early-1968, which succeeded in making NBC to renew, albeit reluctantly, Star Trek for a third season. For decades, network and public were led to believe that it was a spontaneous action organized by Trekkies, but Justman and Solow debunked the "spontaneous" nature of the campaign in their book Inside Star Trek: The Real Story.

Roddenberry - with Trimble and his future wife Majel Barrett - also founded Lincoln Enterprises in 1967, which specialized in selling Star Trek memorabilia to fans. Years later, in 2004, Bjo Trimble has stated, "Actually, John & Bjo Trimble set up the original Lincoln Enterprises. Neither Gene nor Majel had any idea how to set up a mail-order business, while the Trimbles have put together several such businesses. At Creation Grand Slam, Eugene Roddenberry acknowledged our efforts with a big hug & thanks. He is very like his father, who also believed in big bear hugs." Template:Brokenlink}, having added to Herb Solow that Roddenberry founded the company in order to "...give Majel something to do." (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, p. 400) One such memorabilia was unused, spliced up clips from the series' original 35mm film trims, which was taken by Roddenberry from the Desilu vaults. Solow was especially angered by this, accusing Roddenberry with stealing studio property for his own gain. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, pp. 400-401) This actually was somewhat circumferentially hinted at by Majel Barret herself, when she later stated in a 1993, with half-truths interlaced, interview, "Lincoln has been in existence for probably almost a hundred years. It was originally Lincoln Publishing and it was owned by another gentleman many, many years before. His attorney was Leonard Maislich [sic.]. For some reason or another he gave the incorporation to Leonard. I don’t know how it basically happened, but it really belonged to Leonard Maislich until he gave it to me in the early eighties. It [Lincoln] was merely set up for Gene to handle fan mail for Star Trek." (Strange New Worlds magazine, issue 10, Oct/Nov 1993)

No records of a "hundred years" old "Lincoln Publishing" are known to exist and the "gentleman" in question was actually Roddenberry himself as Maizlish had been his life-long attorney. By transferring title to his attorney (who had somehow managed to antedate the company's establishing date to 6 April 1962 through proxy Mort Kessler – hence Barrett's "has been in existence for probably almost a hundred years" remark [6]), Roddenberry had thrown up a smokescreen if the studio ever decided to pursue the matter legally, which however, they never did. As already implied by Trimble and Barrett themselves, there was another, personal reason as well to proceed in this matter, as it was also meant to hide the Lincoln revenues from Roddenberry's soon-to-be ex-wife Eileen as well. It was for these reasons why Lincoln Enterprises was not established as a subsidiary of Roddenberry's official production company Norway Corporation, but as a separate entity. Unsurprisingly and not entirely unjustified as the original Roddenberry couple was still legally married at the time of the incorporation of Lincoln Enterprises, Eileen later found out, and sued all involved parties for damages, resulting in that Maizlish was actually found guilty of "conspiracy to commit fraud" for his part in the deception, though it assessed no punitive damages against him. Kessler, incidentally, settled out-of-court with Eileen. [7] Even staunch Roddenberry supporter Trimble could not refrain herself from calling Roddenberry a "conniver" at one point. [8]

NBC canceled Star Trek definitely in February 1969, despite a second, (but weaker, arguably due to the perceived drop in quality of the last season) letter campaign. [9] Production on the series ceased in June of that year, leaving the entire production at US$4.7 million in debt. (Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, p. 399)

After Star Trek was canceled, Paramount Television wanted to sell Roddenberry all rights and title to the series for US$100,000-$150,000, but he, knee-deep steeped in the fallout of his bitter and costly divorce from Eileen, was nowhere near able to raise this amount on his own. (Star Trek: The Next Generation - The Continuing Mission, p. 2; NBC: America's Network, p. 220) Though Star Trek-lore has it that Roddenberry staunchly held on to his complete faith in his creation, this was actually contradicted during the divorce proceedings, as it showcased his despondency over the apparent failure of his creation. The considerable level of despondency was evidenced by the fact that he, during the proceedings, offered to sell Eileen his share of Star Trek for US$1,000 in exchange for waiving the rights of any and all revenues from future projects Roddenberry might embark on. Eileen declined, astonishingly perhaps in hindsight, but understandable at the time as the Original Series was not to turn in a profit for the coming decades, that is, for Roddenberry at least. Even as late as 1972, Roddenberry reiterated the offer to his by now ex-wife in a subsequent alimony hearing, but again she declined. Represented by Maizlish, Roddenberry's divorce was finalized in July 1969. [10]

Roddenberry actually had already left the couple's house the year previously, on 9 August 1968, a mere two weeks after the first marriage of their daughter Darleen. In effect, he had planned to divorce his wife even earlier, but postponed that action as he felt that he would not have enough time and energy to deal with both the divorce and the production of Star Trek, which had been renewed for a second season. (Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, pp. 352-353)

For Star Trek's 25th anniversary, two months before his death, Roddenberry gave TV Guide a list of his top ten favorite episodes. One might assume that these most clearly represented his vision of what Star Trek should be:

- "Amok Time"

- "Balance of Terror"

- "The City on the Edge of Forever"

- "The Devil in the Dark"

- "The Enemy Within"

- "The Menagerie, Part I" and "The Menagerie, Part II"

- "The Naked Time"

- "The Return of the Archons"

- "Where No Man Has Gone Before"

- "The Trouble with Tribbles"

Other works

After the original Star Trek ended, Roddenberry ventured on numerous other projects, virtually all of them turning out to be failures. In 1968, Roddenberry was contracted to write and produce two feature films for National General Pictures, but the films were never made. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, p. 406) Hired by his former Desilu boss Herb Solow (who was fond of Roddenberry, but could not abide with his antics when it interfered with production), he produced and wrote the screenplay for Roger Vadim's, lukewarmly received, 1971 MGM film, Pretty Maids All in a Row, which featured James Doohan, William Campbell, and his daughter Dawn Roddenberry in the cast. Solow arranged for Roddenberry a hitherto unheard-of writer's fee of US$100,000 dollar. However, as producer, Roddenberry was woefully inept in controlling the antics of director Vadim, causing the production to run both over-time and over-budget. It further marred his reputation as producer, and it came back later to haunt him. Pretty Maids was the first of only two major theatrical motion pictures Roddenberry ever worked on. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 2nd ed, p 420) The favor Solow provided Roddenberry, by arranging his, for the times, substantial writer's fee, came as a godsend for the Roddenberry/Barrett couple, as they were now down on their luck, eking out a meager existence through the Lincoln Enterprises memorabilia sales, supplemented by Star Trek conventions attendance fees only, and also explaining why Roddenberry made the second offer to sell his ex-wife his share in Star Trek. At the time Roddenberry faced a US$2,000 monthly alimony obligation, as well as a mortgage. (Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek, p. 140)

In 1973, he wrote and produced a science fiction pilot entitled Genesis II, which featured Mariette Hartley, Ted Cassidy, Percy Rodriguez and his now-wife, Majel in the cast, costumes by William Ware Theiss, and was photographed by Jerry Finnerman. It was not picked up as a series, and a year later Roddenberry made another pilot out of the same idea, titled Planet Earth. This time Robert Justman served as producer, Marc Daniels as director, and the cast included Diana Muldaur, Ted Cassidy, Majel Barrett, Craig Hundley, Patricia Smith, and again costumes by Theiss. However, this pilot wasn't picked up by the network either, nor was its final variant, the 1975 pilot Strange New World.

Concurrently in 1973, Roddenberry made another failed sci-fi pilot, The Questor Tapes, which starred Robert Foxworth as an android, Questor, searching for his origins and creator. The pilot was directed by Richard Colla and also featured Majel Barrett and Walter Koenig. It was co-written by fellow Star Trek producer Gene L. Coon. The Questor Tapes was not picked up as a series, although its basic concept was reworked into the character of Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Actually, Foxworth's lead role was promised by Roddenberry to Leonard Nimoy, but overruled by the studio, Roddenberry failed to inform Nimoy of this, who had to learn this from a third party. Nimoy, already preparing for the role, never forgave Roddenberry for this and the already strained relationship between the two men, which had started amicably enough at the beginning of The Original Series, accelerated its decent in animosity. It was an example of Roddenberry's recurrent character flaw of being unable to be the bearer of bad news, which Robert Justman and David Gerrold, among others, were to be confronted with as well. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, p 420) Before returning to Trek, Roddenberry made a fourth unsuccessful TV pilot, Spectre in 1977, about a detective involved in witchcraft and other occult phenomena. This pilot was co-written by Samuel A. Peeples, again featuring Majel Barrett, and which again demonstrated that Roddenberry has never shied away from nepotism.

The series that never was

Roddenberry with his two personal assistants, Susan Sackett and Ernie Over

Roddenberry interviewed by Entertainment Tonight in 1991.

Roddenberry approached Paramount as early as 1973 with the idea for a Star Trek feature film, and in the following years the concept went through several revisions and various incarnations (see: Star Trek: The Motion Picture: Production history), from feature film to television movie to series, and back again.

By June 1977, Star Trek was to become a television series again. Paramount attempted to launch a new series, tentatively titled Star Trek: Phase II, to be the "flagship" programme for their planned television network. Construction on the sets started in July, and the writers' and directors' guide was published in August. The original cast, except for Leonard Nimoy (officially for reasons of not willing to commit to the strains of a weekly show, but in reality because of his strained relationship with Roddenberry), returned to reprise their roles, along with several new characters, such as Lt. Xon, who would be taking Spock's place, first officer Willard Decker, and navigator Lt. Ilia.

As work was being finished on the sets and costumes, Paramount abandoned the plans for the new network, and eventually the new Star Trek series. Reportedly influenced by the success of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, they decided to turn the television series into Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

The Motion Picture and feature films

The Motion Picture began production in 1978, on which Roddenberry served as producer with director Robert Wise as uncredited executive producer. Production time and costs went highly over the expected, largely exceeding the pre-calculated budget, ending up with the final number of US$44,000,000, which made The Motion Picture the second most expensive film at the time, after Superman: The Movie. Former Paramount studio executive Jeffrey Katzenberg described the project as "a runaway train". (William Shatner Presents: Chaos on the Bridge)

Despite earning US$82,000,000 in domestic gross revenue, the total gross came as a disappointment to the studio, considering the over-budget costs incurred. In one respect Gene Roddenberry was undoubtedly responsible for the over-budget expenditures, which largely stemmed from his incessant and increasingly vicious battles with the aforementioned Harold Livingston, the by the studio appointed producer (already for Phase II), made responsible for the script. Unable to let go of his vision of Star Trek – of which he was now zealously protective – and stubbornly adhering to storylines he himself, and nobody else, had conceived, Roddenberry was almost from the start at loggerheads with Livingston, resulting in a continuous series of increasingly vicious battles over story outline and script rewrites and re-rewrites, often performed surreptitiously by Roddenberry. The ongoing creative battle lasted for almost two years and proved to be particularly detrimental to the production, aside from entirely destroying the relationship between the two men. Having resigned no less than three times from the production, Livingston had later tersely stated on the occasion of his first departure, "By the time I left, Gene and I were ready to kill one another. I couldn't stand the son of a bitch, so I left." However, by early October 1978, Wise (thoroughly fed up with the production delays due to Roddenberry's inability to turn in a completed script), Shatner, Nimoy, and Katzenberg staged, what can only be described as a coup, and effectively removed Roddenberry from creative control, which was entirely handed over to the recently reappointed Livingston. From there on end, Roddenberry was executive producer in name only. (Star Trek Movie Memories, 1995, pp. 67, 97, 105-111) While many other and more prominent factors interplayed with the overexeeded costs as well, the studio mainly blamed Roddenberry – considered a thorn in their side since the days of The Original Series – for the failure, which provided a good opportunity for them to remove him from creative control entirely and definitively. (see: Star Trek: The Motion Picture: Costs and revenues)

For the subsequent five Star Trek films, Roddenberry was given his own office at the studio and a formal title of "Executive Consultant", which meant that directors and creative staff could ask for his opinion on the project, but his advice was not needed to be taken. David Gerrold typified his new position as "an emeritus status", but added that he was concurrently from now on considered by the industry as "a has-been". (William Shatner Presents: Chaos on the Bridge) And indeed, none of the directors and producers actually consulted for real with Roddenberry regarding their projects, especially Producer Harve Bennett (who loathed Roddenberry [11]) and Director Nicholas Meyer (with whom Roddenberry had a vicious run-in shortly before his death, over perceived racism in regard to the Klingons in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. [12]), both responsible for the three most successful outings of the Original Crew films, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home and The Undiscovered Country, which were the ones, somewhat unsurprisingly, that were most vehemently, but unsuccessfully, resisted by Roddenberry. Most ironically, it was the much reviled fifth movie, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier and directed by William Shatner (who likewise did not consult with Roddenberry), which approximated Roddenberry's atheistic world view the most and which was very reminiscent of his own 1975 original The God Thing movie script, heavily reworked later on to become In Thy Image, ultimately the basis for The Motion Picture. However, not being written by him personally, the movie was vehemently resisted by Roddenberry nonetheless, going even as far as having his attorney Maizlish prepare legal procedures against co-writer Shatner. Legal procedures did not materialize but a thoroughly chagrined Roddenberry ordained the movie as being "apocryphal", readily accepted by the more puritanical elements of Star Trek fandom. (Star Trek FAQ 2.0, chapter 13; Star Trek Movie Memories, 1995, pp. 283-284)

Essentially "bumped upstairs", Roddenberry as Star Trek creator, was still compensated handsomely by the studio though, having profited little, if any, from The Original Series previously, save for the revenues stemming from memorabilia sales through Lincoln Enterprises and his Star Trek conventions attendance fees. (William Shatner Presents: Chaos on the Bridge) Actually, around the time Roddenberry entered into the subsequent movies deal with Paramount (a different one than his 1978 Motion Picture net profit sharing contract, itself revised from the 1965 Original Series contract, allowing for a possible new television series, that however never materialized), he was at loggerheads with the studio over the Original Series net profit sharing agreement. Previously, he had surrendered any and all legal title to The Original Series, save for his "Created By"-credit, in return for a full third of the profit made by that series through syndication, according to author James Van Hise. But by 1981, Roddenberry was still led to believe by the studio that the Original Series was still deeply in the red by as much as US$1 million dollar – or US$500,000 by 1982, again according to Van Hise (The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry, p. 58) – as supposedly "proven" by doctored account statements handed over to him. Roddenberry instructed his attorney Maizlish to start legal proceedings in order to be given access to Paramount's records, seemingly to no avail at the time. "The greatest science fiction in show biz is in the accounting", Roddenberry declared chagrined, referring to the infamous "Hollywood accounting" industry phenomenon (for a more detailed treatise on the phenomenon, please refer to Paramount Pictures: Footnote 2). (Starlog, issue 43, p. 14) Roddenberry had justified reasons to be suspicious, as it seemed unlikely that the by Variety magazine of 2 December 1991 reported net syndication profit of US$78 million dollar in early 1987 was only realized in the intervening six years. While it was at the time unknown what the outcome of the legal proceedings were, it was very much conceivable that Roddenberry and the studio settled their Original Series accounts on that occasion, since it marked the time that Roddenberry actually became affluent because of Star Trek, as was evidenced by the substantial estate that his wife Majel left upon her death in 2009.

That this had actually been the case, became apparent in the California Court of Appeal transcripts of 30 September 1994, docket number B074848, chronicling the ongoing battles between Roddenberry (after his death, wife Majel and son Rod) and his first wife Eileen, who for decades fought tooth and nail to claim half of all the Star Trek revenues. The document specified that Roddenberry received his very first Original Series US$850,000 profit distribution from Paramount in June 1984, followed by disbursements of US$1,842,000 in February 1986, US$780,000 in June 1986, US$924,000 in January 1987 and US$$945,000 in July 1987. Of this amount Roddenberry transferred close to $$2 million dollar to his ex-wife, withholding $750,000, ostentatiously on behalf of their two daughters. Unsurprisingly, Eileen sued him for more; to paraphrase Spock, the court transcripts made for "fascinating" reading. [13] Incidentally, Eileen's case was decided on 16 April 1996, when it was ruled that she was only entitled to half the revenues stemming from The Original Series, not those of any later Star Trek productions. Norway Corporation was given a punitive award, payable to Eileen, as they only transfered the shortfall of the Original Series revenues a mere few days before the trial's start. However, before the ruling, the studio had from June 1988 until then, on the basis of previous lawsuits, split Roddenberry's profit share, including those for the movies and The Next Generation and transferred a full third directly to Eileen when making profit share disbursements (having received a total of US$7.8 million dollar by January 1993), and it has not become clear whether or not she had to restitute those pertaining to the movies and Next Generation, or that they were to be settled with the shortfall of those from the Original Series, of which she had only received a third. [14]

The Next Generation

Roddenberry on set of The Next Generation

In 1986, with Star Trek's 20th anniversary coming soon, and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home hitting the theaters, then Paramount Television Group President Mel Harris decided it would be profitable to launch a brand new Star Trek series. Originally, studio executives wanted to create the series without Roddenberry's involvement, but eventually they agreed that the Star Trek creator should be on board for the project. Roddenberry and his lawyer, Leonard Maizlish agreed on a deal with the studio, which included a "high figure compensation" for Roddenberry, according to Paramount Network Television President John S. Pike. Pike's "high figure compensation" consisted of a US$1 million dollar sign-on bonus, besides a considerable regularly salary, which consisted of US$9,000 per episode, multiplied for eight syndication runs, augmented with US$5,000 legal/administrative fee per episode for Norway Corporation. This amounted to US$77,000 per episode or over US$2 million dollar per season. Additionally Roddenberry arranged a profit sharing deal, where it was stipulated that he was to receive 35% of the adjusted gross (not net as back in 1965, thereby avoiding the "Hollywood accounting" trap) profits derived from the series. Roddenberry celebrated his return to Star Trek by purchasing a new, US$100,000 Rolls-Royce. Incidentally, the studio declared The Next Generation "in the profit" on 21 January 1993, after his death, and announced the start of profit distribution, followed by a US$6.8 million dollar disbursement to Norway and Eileen Roddenberry the following month. (William Shatner Presents: Chaos on the Bridge; Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek, p. 220; [15])

Noted for his loyalty to co-workers he implicitly trusted (already evidenced by his time and again hiring of actors he had worked with before, for his numerous projects over the past decades), Roddenberry, back again at the helm, was determined to bring back as many production staff members from The Original Series as possible to develop and produce the new show, which he had actually already intended to do, and partially did, on the ten years earlier, but ultimately abandoned Phase II television series. These included producers Robert Justman, Edward K. Milkis, as well as writers D.C. Fontana and David Gerrold, all of them brought in first by Roddenberry in October 1986 to form the original production nucleus for the new series, to be followed by several others at later times. (Star Trek: The Next Generation - The Continuing Mission, pp. 9-11) Star Trek: The Next Generation premiered in September 1987 in first-run syndication with the two-hour pilot "Encounter at Farpoint". For all his human fallacies and/or creative, political and interpersonal shortcomings, Roddenberry has also been renowned throughout his life for his more likable character traits as well as for his good-natured practical jokes, which occasionally back-fired on him. Affable and amiable to persons he himself liked and trusted, Roddenberry had an uncanny knack of endearing himself to people. This was exemplified by his glee to be reunited with his Original Series veteran friends, when he walked into the offices of Fontana, Milkis, Gerrold and Justman one day, early in the production of The Next Generation, and, without uttering a word, handed them a US$5,000 bonus each. [16] Though Justman left after the first season on the account of Maizlish, he had nothing but praise for Roddenberry himself, "It was wonderful working with Gene again, though. He was affectionate like he had never been before. Gene was really, really affectionate, almost as if — no, I think it was because he sensed that his end wasn't that far off, and he had a second chance at a relationship with me that never could have happened otherwise, and he wanted to make up for some of the disappointments he had caused me." Justman was referring to him not being invited back to Phase II - The Motion Picture, though Roddenberry had intended to do so. He was however, overruled by the studio, but, typically, Roddenberry could not bear to inform Justman of this, not returning his phone-calls when the latter reported for work. (Starlog, issue 228, p. 59; Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, p. 432)

The first season could be described as a huge turmoil and struggle for power, which were in no small part due to Roddenberry's ill health, aggravated by alcohol and substance abuse (prior to starting his work on the new series, Roddenberry had to be admitted in late summer 1986 into a rehab center to kick his habits). Maizlish, arguably overzealously protecting his client's interests, convinced an ailing and increasingly paranoid Roddenberry that others were lurking to stab him in the back, and managed to get rid of all the Original Series veterans who initially worked on the show. Going as far as rewriting scripts without any Writers Guild of America license or permit, and secretly lurking into other people's offices, Maizlish was considered a main destructive force behind the scenes, and eventually got banned from the Paramount lot. (William Shatner Presents: Chaos on the Bridge, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story) Whether or not Maizlish had his client's interests truly at heart, he had done him a great disfavor as the departure of the Original Series veterans had a profound effect on Roddenberry according to Gerrold, "Gene was crying because all of his friends were gone. It was because Maizlish chased them away." [17] Considering the deep emotional attachment Roddenberry had for his Original Series friends, who were the very first staffers he had brought in to form the original October 1986 production nucleus for The Next Generation, has made Maizlish's attitude towards Gerrold, Fontana, Justman and Milkis all the more inexplicable. The now friendless Roddenberry was subsequently left dangerously exposed to studio politics at which he was notoriously inept. Already during the first two seasons of The Original Series, it had been Herb Solow who ran interference for Roddenberry and the studio, but once the former was gone, so was Roddenberry, and during the production of Phase II–The Motion Picture, Roddenberry again had his share of run-ins with the studio. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, pp. 371-375) "Gene didn't like Rick [Berman], at all. But Rick was installed on the show by the studio as a way to keep a control on the show...to keep the budgets in line, make sure that the scripts were done. Ultimately, Berman ended up in control rather than Maizlish because Berman played the politics of the studio more effectively.", Gerrold elaborated further. [18]

In mid-Season 1, Roddenberry appointed Maurice Hurley as showrunner, and, while still being active overseeing the series, with his failing health, he eventually largely retired from daily production business. Yet, aggravated by the 1988 Writers Guild of America strike, the tail end of the first season and most of the second season was marred by infighting among the writing staff, in which Hurley had center stage. Roddenberry himself, undoubtedly experiencing a severe case of déja vu from his previous dealings with Harold Livingston during the production of Phase II-The Motion Picture, was deeply embroiled with Hurley and other writers, who wrote stories he felt were not in concordance with his vision on Star Trek. Mel Harris, who unlike all of his (preceding) studio executive colleagues, was a Roddenberry supporter (in public at least), had been on record stating, "[W]e had a hard time keeping writers on the show....[A] lot of the writers that were available [in 1986] were coming off of cop shows and...wanted to do bang-bang, shoot-tern-ups or car chases, let's have the space ship run around and...shoot the bad guys, and Gene had to go back in and rewrite many, many of the early scripts because they simply didn't fit the premises that were outlined in this bible." [19] From the third season onward, Berman (originally appointed as "Supervising Producer" by the studio, who, besides Harris, had all but forgotten Roddenberry's behavior during the production of The Motion Picture, to "watch over" Roddenberry's antics) and Michael Piller were made executive producers, and became responsible for running the series, and eventually the entire franchise.

Legacy

The launch of the Columbia carrying the ashes of Roddenberry.

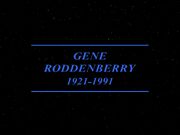

Memoriam credit for Gene Roddenberry during the opening of TNG: "Unification I" and TNG: "Unification II"

On 6 June 1991 shortly before celebrating the 100th episode of The Next Generation the Producers Building at the former Desilu studio lot was renamed "Gene Roddenberry Building". Paramount Television president Mel Harris held a speech and during the ceremony William Shatner and Patrick Stewart said a few words about Roddenberry.

On 24 October 1991, Gene Roddenberry passed away, succumbing to cardiac arrest. At the time of his passing, Roddenberry was survived by his wife Majel, their son Eugene "Rod" Roddenberry Jr, his two grown daughters from his previous marriage to Eileen (who never remarried), Dawn and Darleen Roddenberry (both sisters had uncredited appearances as two of the unnamed Only girls in the Origianl Series episode "Miri"; Darleen tragically perished, almost to the day, four years later in a car accident), and two grandchildren by Darleen.

The ashes of Roddenberry were aboard the space shuttle Columbia during its start from the Kennedy Space Center on 22 October 1992.

Roddenberry served as a member of the Writers Guild Executive Council and as a Governor of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. He held three honorary doctorate degrees: Doctor of Humane Letters from Emerson College (1977), Doctor of Literature from Union College in Los Angeles, and Doctor of Science from Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York (1981).

Eugene Roddenberry, Jr. currently heads the Roddenberry.com website which is also the main site for Lincoln Enterprises, and is "Consulting Producer" for the fan film series Star Trek: New Voyages.

The legacy of Star Trek, as created by Gene Roddenberry, continued to grow as the newest series, Star Trek: Enterprise, joined Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Star Trek: Voyager. The Next Generation evolved into a feature film series, debuting in 1994 with Star Trek Generations.

Other shows of Roddenberry's design include Earth: Final Conflict and Andromeda, the latter of which based on the aforementioned television pilots Genesis II of 1973, and its 1974 and 1975 reworked versions, Planet Earth and Strange New World, respectively.

Roddenberry canon

A minority of purist fans advocate a "Roddenberry canon" to denote what episodes Star Trek's creator approved of as "official." Defining such a concept is elusive, as Roddenberry was known to change his views over the years. The Original Series would seem to be part of this canon, comprising 79 episodes, plus the un-aired first pilot "The Cage". He rejected The Animated Series as apocryphal, along with elements of two films, The Final Frontier, and The Undiscovered Country. At the time of his death, 110 episodes of The Next Generation had completed production, from "Encounter at Farpoint" through "New Ground". This leaves 190 episodes of Star Trek as part of the supposed Roddenberry canon, along with the first four films, and most of films five and six. Adhering to this view would mean rejecting 536 episodes, as well as at least four films, as there have been 726 episodes of Star Trek produced to date, along with twelve motion pictures.

Trivia

- Gene Roddenberry had a second cousin twice removed named Mary Sue Roddenberry. Ironically, and probably by sheer coincidence, the widespread fan fiction term "Mary Sue", which is used to describe overly perfect original female characters, has its origins in the person of Lt. Mary Sue, a character in the satirical 1974 short Star Trek story by Paula Smith called "A Trekkie's Tale".

- Roddenberry gave his middle name to one of the characters of Star Trek: The Next Generation – Wesley Crusher. (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, p. 14) His middle name was also used as the last name of the TOS character Robert Wesley, which was also a pseudonym Roddenberry used in his early writing career. (Star Trek Encyclopedia 1st ed., p. 374) In addition, after his death, the creators of Voyager used Roddenberry's full first name as the middle name of reformed renegade officer Thomas Eugene Paris. (Star Trek Encyclopedia 3rd ed., p. 348)

- In "The Big Goodbye", an illustration of Gene Roddenberry was seen when Data was assimilating the Dixon Hill novels. This illustration was the copy of a photo of Gene Roddenberry.

Credits

Roddenberry's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Roddenberry receives a "Created by" credit on episodes of The Original Series and The Next Generation. In addition he is credited on all episodes of Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Enterprise, all the movies, and many Star Trek computer games such as the Elite Force series and Star Trek: Bridge Commander, via the phrase "Based upon Star Trek, created by Gene Roddenberry".

The first two Next Generation episodes aired after his death, "Unification I" and "Unification II" begin with the title card "Gene Roddenberry 1921 - 1991". Also, the film The Undiscovered Country begins with the credit, "For Gene Roddenberry". The credits for Star Trek end with "In memory of Gene Roddenberry and Majel Barrett Roddenberry". Several other Trek related products, including the video game Star Trek: 25th Anniversary include special thanks credits in honor of Roddenberry.

Roddenberry also receives credit for writing lyrics to the Original Series main title theme, although these lyrics were never recorded in connection with the series. In the reference book Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (1997, p. 185), Herb Solow and Robert Justman allege that Roddenberry, who had no musical experience of any kind, wrote words to Alexander Courage's theme for the show solely to accrue royalties that were required to be paid to the lyricist. In doing so, he effectively cut Courage's royalties in half, as the composer would otherwise have received all royalties accruing from the theme. Courage was outraged on this, and left the production, only to return to score two episodes in the third season as a courtesy to Robert Justman. However, Courage mellowed over the years, has stated in his twilight years, "There wasn't any rift, really, with Gene. What happened with Gene was a I got a phone call once...it was Gene's lawyer, [Leonard] Maizlish. He said, "I'm calling you to tell you that since you signed a piece of paper back there saying that if Gene ever wrote a lyric to your theme that he would split your royalties on the theme." Gene and I weren’t enemies in any sort of way. It was just one of those things...I think it was Maizlish, probably, who put him up to doing it that way, and it's a shame, because actually if he'd written a decent lyric we could have both made more money." [20] Having corresponded with Courage at a later point in time, this was another example of Roddenberry's more amiable character traits; whenever he felt that he had aggrieved someone, he often felt the need to make amends afterwards, like he had done with Robert Justman as described above. The Roddenberry/Maizlish duo had actually tried to do something similar with Leonard Nimoy's first vinyl album recording, Mr. Spock's Music From Outer Space, which marked the beginning of the descent into animosity of the relationship between Roddenberry and Nimoy. With Nimoy however, Roddenberry was not able to mend fences, due to a continuous series of subsequent incidents (such as in the instance of The Questor Tapes, mentioned above), which kept bedeviling any possible chance of reconciliation. After The Motion Picture, were he finally had his pound of flesh by conspiring against Roddenberry, Nimoy broke off any communication between them, and both were not seen together afterwards, save for the subsequent five Original Crew films at official studio press presentations. Nimoy has not been present at any commemorative event involving Roddenberry, nor was he present at his funeral.

Roddenberry also credited himself as the co-author of the reference book The Making of Star Trek, receiving half the royalties, which was written by Stephen E. Whitfield, and given to Roddenberry to make his corrections and edits, though he had never the time to do so, because of production deadlines. While virtually every other person (like the above-mentioned Courage), before or after, who had been cajoled out of their royalty shares in a similar way by Roddenberry, became livid with him, Whitfield (aka Stephen Edward Poe), was the notable exception. Not minding surrendering half the book royalties, Whitfield got along very well with Roddenberry, not in the least due to their shared aviation background, and was grateful for the chance he was given to start his writing career as a book author. The fact that he had written the very first Star Trek reference book (and a very successful one at that) had been a source of immense pride for him for the remainder of his life. (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, 1997, pp. 401-402)

- Writing credits

- TOS:

- "The Cage"

- "Mudd's Women" (Story) (Season 1)

- "Charlie X" (Story)

- "The Menagerie, Part I"

- "The Menagerie, Part II"

- "The Return of the Archons" (Story)

- "Bread and Circuses" (with Gene L. Coon) (Season 2)

- "A Private Little War" (Teleplay with Gene L. Coon)

- "The Omega Glory"

- "Assignment: Earth" (Story with Art Wallace)

- "The Savage Curtain" (Teleplay with Arthur Heinemann, Story) (Season 3)

- "Turnabout Intruder" (Story)

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture (story, uncredited)

- TNG:

- "Encounter at Farpoint" (with D.C. Fontana) (Season 1)

- "Hide and Q" (Teleplay with C.J. Holland)

- "Datalore" (Teleplay with Robert Lewin)

- TOS:

- Producer credits

- TOS: (executive producer; producer)

- "The Cage" to "The Enemy Within" (producer)

- "The Man Trap" (credited as executive producer and producer)

- "Charlie X" to "Dagger of the Mind" (producer)

- "Miri" to "The Menagerie, Part I" (executive producer)

- "The Menagerie, Part II" (producer - credit for "The Cage")

- "Shore Leave" to "The Omega Glory" (executive producer)

- "Assignment: Earth" (producer)

- "Spectre of the Gun" to "Turnabout Intruder" (executive producer)

- TAS (executive producer)

- Star Trek films:

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture (producer)

- TNG (executive producer) from "Encounter at Farpoint" to "Time's Arrow"

- (posthumous credit only from "Violations" to "Time's Arrow")

- TOS: (executive producer; producer)

- Executive consultant credits

- Acting credits

- TOS:

- "Charlie X" as the voice of the galley chef (uncredited) (Star Trek Encyclopedia, etc.)

- In addition, Roddenberry hosted the video release of "The Cage" and an image of him appeared as Captain Robert April in the Star Trek Encyclopedia. He can also be heard (along with Majel Barrett and other production people) in the background intercom chatter in "Where No Man Has Gone Before" (and subsequent episodes reusing the same sound tracks).

- TOS:

Interviews

Interviews of Roddenberry were part of the following specials:

- The Star Trek Saga: From One Generation To The Next, interviewed on 20 September 1988

- TNG Season 1 DVD special feature "The Beginning"

- TNG Season 1 DVD special feature "Memorable Missions"

- TNG Season 2 DVD special feature "Mission Overview Year Two" ("Diana Muldaur", "Whoopi Goldberg"), footage taken from The Star Trek Saga...

- TNG Season 2 DVD special feature "Selected Crew Analysis Year Two", footage taken from The Star Trek Saga...

- TNG Season 4 DVD special feature "Mission Overview Year Four" ("Celebrating 100 Episodes"), interviewed by Entertainment Tonight in 1991

- TNG Season 5 DVD special feature "A Tribute to Gene Roddenberry" ("Gene Roddenberry Building Dedicated to Star Trek's Creator", "Gene's Final Voyage"), interviewed on 6 June 1991 and footage taken from The Star Trek Saga...

- To Boldly Go

- "Gene Roddenberry - The Creator of Star Trek: The Next Generation", The Official Star Trek: The Next Generation Magazine Vol. 1, pp. 4-9, interviewed by Dan Madsen, John S. Davis and Dan Dickholtz

- "Eternal Questions", The Official Star Trek: The Next Generation Magazine Vol. 11, p. 15

Further reading

- The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry, 1992

- Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation, 1994

- Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek, 1994

- Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, 1994

- Inside Trek: My Secret Life with Star Trek Creator Gene Roddenberry, 2002

Footnote

- ↑ For other pilots among Star Trek personnel, see James Doohan, Franz Bachelin, Michael Dorn, Matt and John Jefferies, Harold Livingston and Stephen Edward Poe.

External links

- Gene Roddenberry at Wikipedia

- Template:IMDb-link

- Gene Roddenberry Biography and Stories at TV.com

- Gene Roddenberry at Memory Beta, the wiki for licensed Star Trek works

- Gene Roddenberry at SF-Encyclopedia.com